The word privacy isn’t in the Constitution. Yet privacy has become one of the most important values protected by the Bill of Rights.

Privacy is the right to get away. To keep people out – out of your house, out of your business, out of your papers, out of your life. It is the right to be let alone, as Louis Brandeis put it. The right to be forgotten, as the Europeans now say.

And it’s more than that. It’s individual integrity, autonomy, dignity and control of intimate aspects of life – the right to make personal choices about whom to marry, whom to live with, what sexual identity to take, where to send one’s children to school, whether to have a baby or not to have a baby.

Over the past century the legal system has erected legal walls to protect privacy from the onslaught of modern communications technology. But those legal walls are like a Maginot line that is no match for ubiquitous mobile technology that rushes past like an invading army.

False claims, gossip and innuendo flood the Internet without any way of punishing the websites that contain the garbage. Too many people post too much gossip, innuendo and fake news on too many websites for anyone to be held accountable.

Technology can recognize faces in stadiums. Google photographs your house from the air and from the street. NSA and now its private communications partners collect the metadata of all your telephone calls. “Stingray” technology, used in St. Louis, allows police to ping a cell phone from outside a building, enabling them to figure out where the phone is, down to the exact room.

Two privacies

There are at least two notions of privacy relevant to the Bill of Rights. One is the protection against government snooping and illegal searches by government agents. The Fourth Amendment’s ban on unreasonable searches and seizures is the basic protection against this kind of invasion of privacy.

In recent years, the Supreme Court has broadened this protection by requiring a search warrant to place a GPS device on a suspect’s car or to search the cell phone of a person under arrest. Both decisions showed that the court is concerned about the privacy implications of modern technology.

The other notion of privacy is the right to control one’s body and family. Because the word privacy doesn’t appear in the Constitution, the Supreme Court decisions finding the right have been highly controversial, especially so because they involve abortion, contraception and same-sex marriage.

The legal sources of the constitutional right of personal liberty are the due process clauses of the Fifth and 14th Amendments. Both amendments say that the government cannot deprive people of their “life, liberty or property, without due process of law.” The Fifth Amendment applies to the federal government and the 14th Amendment to the states.

In lawyers’ language, the disagreement is over what is called “substantive due process.” Due process clearly requires procedures that are fair in form. The question is how much of the substance of liberty should be included in due process.

In the same-sex marriage decision of 2015. Justice Anthony M. Kennedy wrote that the court had to apply new insights to the Constitution. “The nature of injustice is that we may not always see it in our own times,” he wrote. “The generations that wrote and ratified the Bill of Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment did not presume to know the extent of freedom in all of its dimensions, and so they entrusted to future generations a charter protecting the right of all persons to enjoy liberty as we learn its meaning.”

This new meaning encompasses a couple’s right to “define and express their identity and to exercise the right to personal choice regarding marriage that is inherent in the concept of individual autonomy.”

In his dissent, Chief Justice John G. Roberts wrote that “allowing unelected judges to strike down democratically enacted laws based on rights that are not actually in the Constitution raises obvious concerns about the judicial role.” Roberts called it pretentious for five lawyers on the Supreme Court to dictate to the country a new meaning of an ancient institution.

It is a debate relevant to the recurring question of whether the Constitution is a living document, as envisioned by Justice William J. Brennan Jr., the 20th century liberal spark plug of the court. This means that the words of the Constitution take on modern-day meanings. Even if “equal protection” didn’t include women when written, it does today.

Justice Antonin Scalia favored a dead Constitution that means what the authors said when they wrote it. Scalia opposed a broad reading of the liberty protected by due process.

Under the broader interpretation of due process favored by Brennan, those few words in the Fifth and 14th amendment have enormous heft. They:

- Incorporate the major amendments to the Bill of Rights against the states, meaning that the states have to abide by them – which they didn’t have to do until the 1930s.

- Protect the liberty of the individual to make decisions about contraception, abortion, same-sex marriage and other intimate personal and family matters.

- Import from the 14th amendment into the 5th Amendment the 14th amendment’s equal protection promise. The original Bill of Rights had no equality guarantee, but the court has said that due process imports the equality guarantee into the Fifth Amendment, binding the federal government. This was the basis for declaring school desegregation in D.C. unconstitutional and for later declaring the federal Defense of Marriage Act unconstitutional for discriminating against same-sex couples.

The enormous constitutional weight that has been put on due process is one reason that President-elect Donald Trump’s picks to the Supreme Court are important. Two justices with Scalia’s narrow interpretation of due process could read abortion and same-sex marriage out of the Constitution.

Historical roots

British troops invading the privacy of the home were a leading grievance among the colonists, helping spark the Revolutionary War. The colonists loathed general warrants and writs of assistance, which allowed broad searches without evidence and permitted ransacking the personal papers. The Fourth Amendment was a response to the colonists’ fury about general warrants.

The American yearning for privacy was broader than a Revolutionary War grievance. One of the reasons people came to the United States was to escape the crowded cities. And one of the reasons that people kept moving west toward the open frontier was their search for privacy and solitude.

But modern communication broke the solicitude – the mail, the Pony Express, railroads, telegraphs, telephones, cameras, motion pictures.

The growth of the penny press and the sensationalism of the yellow journalism at the turn of the 20th century put a premium on the salacious scoop and the gossipy tidbit. At the time, newspapers were growing as fast as

they now are closing. In 1850 there were 100 newspapers with 800,000 readers. By 1890 were 900 newspapers with 8 million readers.

Brandeis and Warren

This was the setting when Samuel Warren, a Boston blue blood, married Mabel Bayard, the daughter of Thomas F. Bayard, senator from Delaware and former candidate for president of the United States.

The press covered the Warren-Bayard wedding in 1883 in great detail. The Washington Post story was headlined: “A Ceremony in the English Style Attended By the Blue Blood of Delaware and Boston.” It commented that the wedding was one “for which there had been hopes and fears, heart flutterings, and silent longings.”

The press went on to report on many of the gatherings between Mabel Warren and Frances Cleveland, Grove Cleveland’s young First Lady.

The press reports on the Warren parties together with the new technology of the movable camera led to Warren and Louis Brandeis writing the most famous law review article in history, advocating a right to be let alone.

The right to be let alone

Brandeis and Warren found a right to privacy in the “right to life.” “The right to life,” they wrote, “has come to mean the right to enjoy life, — the right to be let alone”

Brandeis and Warren left no doubt that they were responding to newspapers and that era’s advance in technology – the movable camera that allowed photographers to take photos of people without permission. They wrote:

“Instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise have invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life; and numerous mechanical devices threaten to make good the prediction that ‘what is whispered in the closet shall be proclaimed from the house-tops.’”

Brandeis and Warren referred to a notorious case involving the dancer, Marian Manola. She objected that a photographer had take her photo her from a theater box as she was playing a role requiring her appearance in tights. The photo prompted her to run off the stage.

Warren and Brandeis wrote: “The press is overstepping in every direction the obvious bounds of propriety and of decency. Gossip is no longer the resource of the idle and of the vicious, but has become a trade, which is pursued with industry as well as effrontery. To satisfy a prurient taste the details of sexual relations are spread broadcast in the columns of the daily papers. To occupy the indolent, column upon column is filled with idle gossip, which can only be procured by intrusion upon the domestic circle.”

Sounding an alarm that one hears today in connection with the Internet, Warren and Brandeis wrote that gossip will eclipse important matters for public attention. They wrote that gossip, “both belittles and perverts. It belittles by inverting the relative importance of things, thus dwarfing the thoughts and aspirations of a people. When personal gossip attains the dignity of print, and crowds the space available for matters of real interest to the community, what wonder that the ignorant and thoughtless mistake its relative importance.”

Warren and Brandeis proposed a tort – a civil lawsuit for damages – to punish invasions of privacy where there was damage. Truth would be no defense.

“The common law has always recognized a man’s house as his castle, impregnable, often, even to his own officers engaged in the execution of its command,” they wrote. “Shall the courts thus close the front entrance to constituted authority, and open wide the back door to idle or prurient curiosity?”

First cases

By the time Brandeis was a justice on the Supreme Court, the new technology raising privacy questions was wiretapping. In Olmstead v. United States in 1928 the court concluded that wiretapping did not violate the Fourth Amendment because it did not involve trespass into a person’s home. “There was no search of the defendant’s houses or offices,” the court wrote.

Brandeis dissented, borrowing a phrase from the law review. “Subtler and more far reaching means of invading privacy have become available to the government.” he wrote. “Discovery and invention have made it possible for the government, by means far more effective than stretching upon the rack, to obtain disclosure in court of what is whispered in the closet.”

Brandeis said that the Framers “knew that only part of the pain, pleasure and satisfaction of life are to be found in material things. They sought to protect Americans in their beliefs, their thoughts, their emotions and their sensations. They conferred, as against the government the right to be let alone – the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized men.”

Not until1967 did the Warren Court overrule Olmstead, deciding in Katz v. United States to protect the privacy of a conversation in a public phone booth.

Court’s development of a right to privacy

During Brandeis’ first decade on the Supreme Court, the right to privacy came up in contexts that did not involve the media but rather in the rights of individuals to control their bodies and family decisions.

The cases involved the right of a school teacher to teach German, the right of Catholic parents to send their children to parochial schools and the right of woman with a low I.Q. to avoid forced sterilization. These decisions about the autonomy of the individual and the family became the constitutional basis of a right to privacy.

Robert T. Meyer was arrested on May 25, 1920 for teaching German to 10-year-old Raymond Parpart. He was sentenced to 30 days in jail and a $25 fine.

Nebraska and 21 other states had passed laws against foreign language instruction in reaction to immigration, in bitterness toward Germans after World War I and in reaction to the Russian Revolution. The Nebraska law said only English could be taught to children before eight grade so that English would become their “mother tongue.” The state claimed it had the power to “compel every resident of Nebraska so to educate his children that the sunshine of American ideals will permeate the life of the future citizens of this Republic.”

The Supreme Court disagreed. It said that the “liberty” protected by the 14th Amendment was more than freedom from bodily restraints. It also included “the right of the individual to contract, to engage in any of the common occupations of life, to acquire useful knowledge, to marry, establish a home and bring up children, to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience and generally to enjoy those privileges long recognized as essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.”

The same angry political atmosphere led to Oregon passing a law in 1922 requiring all children between 8 and 16 attend public schools. Gov. Walter M. Pierce said that if “the character of the education of such children is to be entirely dictated by the parents of such children…it is hard to assign any limits to the injurious effect from the standpoint of American patriotism.”

The Catholic Society of the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary challenged the law. The Supreme Court struck it down writing, “The fundamental theory of liberty…excludes any general power of the State to standardize its children by forcing them to accept instruction from public teachers only.”

The court was not so protective of privacy rights, however, in the shameful sterilization of Carrie Buck. Buck was a young woman in Virginia who was sterilized because she did poorly on an I.Q. test. Half of the white males were categorized as morons under the test. She also was accused of being “promiscuous” based on a pregnancy out of wedlock; actually a relative had raped her.

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, famous for his decisions championing civil liberties, wrote the decision upholding the sterilization. He claimed Buck, her mother and daughter all were mentally defective and declared, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

Griswold v. Connecticut

One of the most famous privacy cases was Griswold v. Connecticut in which the court ruled that laws making it a crime to provide birth control were unconstitutional.

The decision was handed down in 1965, but the controversy had begun in the 1920s. Katherine H. Hepburn the mother of the famous actress, was one of three organizers of a public meeting in 1923 that led to the formation of the Connecticut Planned Parenthood League to fight the law. First attempts failed.

Subsequently, Dr. C. Lee Buxton, head of the Yale Medical School’s obstetrics unit in the 1950s was shocked to discover that he could not prescribe birth control devices for his married patients. He joined forces with Estelle Griswold and Yale law professor Fowler V. Harper.

Griswold was a Junior Leaguer who opened an eight-room birth control clinic in New Haven in 1961. She knew she was likely to be arrested, but that was the point. She wanted to challenge the state law. Griswold was arrested and charged. The criminal complaint said her crime was that she “did assist, abet, counsel, cause and command certain married women to use a drug, medicinal article and instruments, for the purpose of preventing conception.” Both Griswold and Dr. Buxton were convicted and fined $100 each. On June 7, 1965 the Supreme Court voted 6-2 to overturn the convictions.

The court’s decision recognized a constitutional right to privacy for the first time, but no five justices had the same explanation for where they found the right in the Constitution.

Justice William O. Douglas, who wrote the main opinion, reasoned that “specific guarantees in the Bill of Rights have penumbras, formed by emanations from those guarantees that help give them life and substance.” He said that five amendments in the Bill of Rights created these “zones of privacy.” They were the First Amendment’s freedom of association, the Third Amendment’s limits on quartering troops, the Fourth Amendment’s freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures, the Fifth Amendment’s right against self-incrimination and the Ninth Amendment’s reservation of rights to the people.

“We deal with a right of privacy older than the Bill of Rights,” he wrote, “older than our political parties, older than our school system. Marriage is coming together for better or for worse, hopefully enduring, and intimate to a degree of being sacred. The association promotes a way of life, not causes; a harmony in living, not political faiths; a bilateral loyalty, not commercial or social projects. Yet it is an association for as noble purpose as any involved in our prior decisions.”

Three other judges agreed with Douglas but issued their own opinions. Justice Arthur Goldberg expanded on the role of the little used Ninth Amendment. “To hold that a right so basic and fundamental and so deep-rooted in our society as the as the right of privacy in marriage may be infringed because that right is not guaranteed in so many words by the first eight amendments to the Constitution is to ignore the Ninth Amendment and to give it not effect whatsoever,” he wrote.

Two other members of the majority – Justices Byron R White and John Marshall Harlan – said they could not agree with either Douglas or Goldberg. They said that the law violated a liberty protected by due process in the 14th Amendment.

After Griswold

Griswold set the stage for the most important privacy decision of the 20th century – Roe v. Wade. But that decision recognizing a limited constitutional right to an abortion also lacked a clear statement about where to find the unenumerated right to privacy.

Justice Harry Blackmun used equivocal language in explaining where the court found the right to privacy: “The right of privacy, whether it be founded in the 14th Amendment’s concept of personal liberty and restrictions upon state action, as we feel it is, or…in the Ninth Amendment’s reservation of rights to the people, is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.”

The court has struggled ever since to explain where it finds the right of privacy. Justice Douglas’ language about “penumbras” is not used by the court and often is ridiculed.

Justice Kennedy has breathed new life into the 14th amendment’s protection of “equal liberty” in a series of decision striking down same-sex sodomy laws, striking down the federal Defense of Marriage Act and finally establishing the constitutional right to same-sex marriage.

Kennedy doesn’t use the word privacy. He talks about liberty, a word that is in the Constitution. He wrote in the 2015 same-sex marriage decision that “the right to personal choice regarding marriage is inherent in the concept of individual autonomy…Like choices concerning contraception, family relationships, procreation, and childrearing, all of which are protected by the Constitution, decisions concerning marriage are among the most intimate that an individual can make.”

President-elect Donald Trump has said he wants new justices to read Roe v. Wade out of the Constitution but that he has no problem with same-sex marriage. Yet both decisions rest on the same interpretation of the liberty protected by due process. So a decision overturning Roe could lead to the end of constitutional protection for same-sex marriage.

Expectation of privacy

From a legal standpoint, the key question in a privacy case is this: What is a person’s expectation of privacy under the circumstances.

The Supreme Court has ruled that a person does not have an expectation of privacy in a greenhouse on private land that a police helicopter flies over. There is no expectation of privacy in trash bags left at the street. Nor is there an expectation of privacy in metadata of telephone calls that show only who calls whom, but do not include the content of the conversation.

People clearly have no expectation of privacy to protect them from video cameras found at every urban intersection. They are standing on public sidewalks. Nor can they claim their right of privacy was violated if a street photographer gets a shot of a man having lunch with a mistress at a sidewalk café.

But a person’s expectation of privacy is at its maximum in the home. Two Life magazine employees talked their way into the home of a disabled veteran who claimed healing powers. They wanted to expose his practice of medicine without a license. The veteran told one of the Life journalists that she had gotten breast cancer by eating rancid butter and he suggested a remedy using clay. The Life crew took photos in the man’s living room with a hidden camera and secretly recorded his conversation with a hidden microphone. The court found that the veteran had a great expectation of privacy in the home and the Life crew had violated it.

In another much cited California decision, Shulman v. Group W Productions, the Supreme Court of California found that a ride-along crew of TV journalists intruded upon the seclusion of a person who was trapped under a car after a traffic accident on a public road. The TV news crew was reporting on rescues of paramedics and had wired a nurse who crawled under a car and picked up the conversation of the trapped motorist. The motorist had a reasonable expectation that the words spoken while trapped in the car were not for broadcast, the court concluded.

Public disclosure of private facts involves publication of private facts the disclosure of which would be highly embarrassing to a reasonable person and which are not of legitimate pubic concern. Publication of a photo of a woman whose dress was blown up by air jets is an example. Still, the freedom of the press allows news organizations to print the names of juveniles and rape victims if the information was lawfully obtained.

Privacy also is implicated in the “right of publicity,” giving a person the right to make money on his or her own image. A former college quarterback, Sam Keller, sued the Electronic Arts for using his likenesses in a popular video game, NCAA football. The NCAA licenses the likenesses of the players to Electronic Arts. A federal appeals court ruled Electronic Arts had to pay players like Keller to use his likeness.

For much of the period from 1980-2010, the Supreme Court cut back on the privacy a citizen could expect in a police stop on a street. But the proliferation of tracking technology seems to have made the court more sensitive to the privacy considerations of citizens.

Police could traditionally follow a suspect or put an electronic beeper on the suspect’s car to make it easier to track the auto. But in the 2012 decision of U.S. v. Jones, the court ruled unanimously that police could not use GPS tracking to keep an eye on a suspected drug dealer over a month-long period without a warrant. Then in 2014, in Riley v. California, the court unanimously ruled that police could not search a person’s cell phone at the time of the arrest without a warrant.

“Modern cell phones are not just another technological convenience,” wrote Chief Justice Roberts. “With all they contain and all they may reveal, they hold for many Americans the privacies of life.”

The GPS and cell phone cases together suggest that the court is trying to protect the privacy of people against the onslaught of modern communications technology.

National security and privacy

After the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, Congress passed the Patriot Act of 2001, which gave greater priority to security over privacy. The law made it easier for investigators to trace emails and IP addresses of computers. It also made it easier for FBI agents to issue National Security Letters to obtain private information. The Patriot Act made it illegal for libraries to tell people that the government was seeking information about their library habits.

In 2005, The New York Times disclosed that the administration of President George W. Bush had been listening to the content of conversations Americans had with people abroad without a warrant. A number of legal authorities thought this warrantless surveillance violated both the Fourth Amendment and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. The FISA law had set up a secret court to approve interception of conversations involving national security. In response to the Times’ disclosure, Congress loosened the requirements of the FISA court in a way that permits this kind of surveillance.

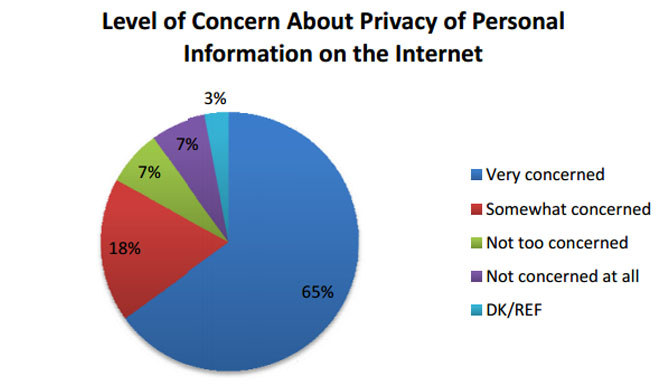

The American people’s attitude toward privacy changed significantly in the wake of Edward Snowden’s disclosures that the National Security Agency is collecting the metadata of all Americans so that it can search the communications of those who may be involved in terrorist incidents.

The disclosures led to reforms that transferred the data collection to the private phone companies, who aren’t covered by the Fourth Amendment.

In May, 2014, the European Court of Justice recognized the so-called “right to be forgotten.” It ordered Google to remove a link to a digitized 1998 article about the foreclosure of a Spanish man’s house for a debt which he later paid. Any law in the United States requiring Google or any other search engine to remove from the Web truthful information previously published could run afoul of the First Amendment.

Looking ahead

The right to be let alone – to be let alone by the government, to be let alone by Google, to be let alone by the tracking technology of modern communications equipment – is fundamental to life. The right of privacy involves a host of decisions that individuals and families make – whom to marry, when and whether to have a child, what sexual identity to take, where to send the children to school, whom to friend on Facebook, what privacy setting to choose on social media, and even where to put the smartphone during dinner or while sleeping or taking a shower.

As the challenges that media and technology pose to privacy grow, the yearning for privacy grows too. Brandeis and Warren’s call for legal protection of the right to privacy has resulted in a regime of law that provides some protection. In addition, the Supreme Court has recognized a right of privacy or of liberty over the past century and in recent years has demonstrated its concern for the threat that new technology poses to privacy.

The open question is whether the judges and the legislators can keep up with the computer engineers and bloggers. On this 225th birthday of the Bill of Rights, it appears unlikely.

No Comments