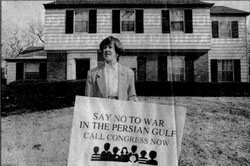

As the third century of the Bill of Rights dawned in Ladue, Mo., Margaret Gilleo was putting a small anti-war sign in a second floor window of her Ladue home. The city’s feisty mayor, Edith Spink, insisted Gilleo take it down to preserve the wealthy town’s aesthetics.

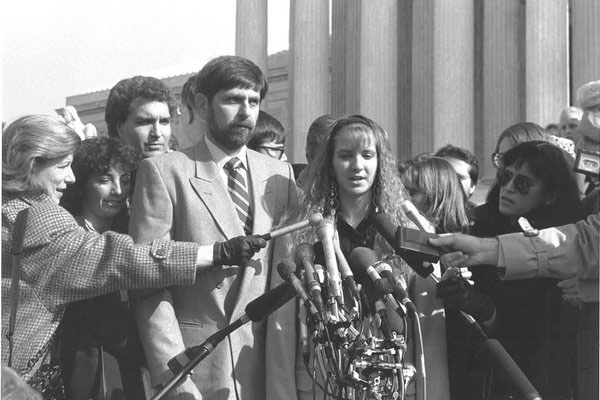

Meanwhile, the Weisman family in Providence, R.I., had taken on the public schools, objecting to the prayer planned for the graduation of their daughter, Deborah, from middle school. “We’re just protecting our rights to be in the public school and not have religious views thrown in our face,” Deborah said.

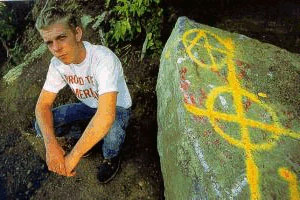

In St. Paul, Minn. the lights were burning all night in the children’s bedrooms to chase away the fear left by the burning cross in the yard of the young Jones family. Grass still wouldn’t grow on the brown spot in the side yard where the cross had burned. Could the Neo-Nazi skinheads who burned the cross be convicted under a city ordinance protecting African-Americans from cross-burning?

And at the University of Virginia, Ronald Rosenberger was challenging the university’s refusal to provide his Christian magazine, Wide Awake, with the funding it provided other student activities. The Jewish Law Students Association and Muslim Student Association got money but not the Christian magazine.

Together, these four important cases from the start of the third century of the Bill of Rights illustrate where the Supreme Court had been and where it was going on the First Amendment.

Gilleo’s sign and the Weismans’ objections to the graduation prayer are the traditional First Amendment case where liberal outsiders challenge conservative authorities and win.

On the other hand, the Joneses’ cross-burning case and Rosenberger’s Christian magazine illustrate a new direction that the court was beginning to take. It was a direction more protective of conservative speech.

The court threw out the conviction of the neo-Nazi skinheads as a warning against political correctness. St. Paul’s law protected minorities, such as blacks, while not protecting other groups, such as veterans. Justice Antonin Scalia was sending a warning to universities that their speech rules couldn’t just protect blacks and women; they had to protect everyone.

And Rosenberger won based on the court’s decision that a university couldn’t discriminate against a Christian group, even if it was trying to avoid the separation of church and state.

In the years since these four cases, arguments protecting conservative speech have prospered.

City of Ladue v. Gilleo

Margaret Gilleo was so dispirited by the impending war with Iraq that she decided not to decorate for Christmas in December 1990. Instead she got a hammer and planted a 2-by-3-foot yard sign reading, “Say No To War in the Persian Gulf, Call Congress Now.”

The reaction was swift.

The sign disappeared. She got a new one. It was knocked down. She called the Ladle police to complain. They said she was the one violating the law, in this case the city’s sign ordinance.

She asked the City Council for a permit. The council unanimously refused and Gilleo found herself in the offices of American Civil Liberties Union lawyer Mitchell Margo the day after Christmas.

U.S. District Judge Jean C. Hamilton ruled that the city’s sign law violated the First Amendment. The city passed a new law, Ordinance 35, stressing its commitment to free speech and “interest in privacy, aesthetics, safety and property values.”

By early 1991, Gilleo had put the 8 1/2-by-11-inch sign in her second floor bedroom window. Ladue said that too was illegal. Hamilton ruled Ordinance 35 unconstitutional like its predecessor.

In the federal appeals court, Ladue argued it had a “unique heritage” like Williamsburg, Va. Malcolm Drummond, a noted city planner from San Francisco, said none of the Midwestern cities where he worked could “compare with Ladue in its aesthetic ambience and privacy.”

Spink, the mayor, led the charge against Gilleo. She acknowledged in a deposition that she’d be more likely to permit a sign that read, “Say No to Drugs” or “Bring Our Hostages Home” than Gilleo’s sign.

The Supreme Court, often closely divided on speech issues, wasn’t divided on this one. It rejected Ladue’s law 9-0.

In the process the court nailed together two traditional Americans values, free speech and private property, and built a high constitutional fence protecting the use of the home to speak.

“It’s a your house is your castle decision,” said Saint Louis University law professor Alan J. Howard said at the time.

Gilleo jubilantly announced she would go home and plant her “Gilleo for Congress” sign in her yard. (She lost) Mayor Spink said she now was worried that “bake sale” and political signs would proliferate.

Praying to someone else’s God

The Independent man on top of the state Capitol in Providence symbolizes the religious freedom that sustained Roger Williams in the winter of 1636 after Massachusetts banished him into the wilderness for “new & dangerous opinions.”

The city became the site for an important Supreme Court decision on religious liberty in 1991.

A few years earlier, hen one of the Weisman’s daughters, Merith, graduated from Nathan Bishop Middle School, a pastor called out for the audience to thank Jesus.

“I felt extremely uncomfortable, that I was in the position to have to stand and worship someone else’s savior,” recalled Daniel Weisman at the time. Weisman was a professor at the University of Rhode Island and non-practicing Jew.

Three years later, in 1989, when daughter Deborah was graduating, Weisman decided to object. He wrote the school describing the previous experience and suggesting no prayer. There was no reply. A teacher eventually sent home a note saying that the school was inviting Rabbi Leslie Gutterman in order to make the Weismans feel comfortable.

“We immediately responded that this was not the issue,” Weisman recalled. “We don’t want to be on the side of the oppression either.”

The Weismans went to court but there was no decision before graduation day. Deborah, wearing high heels for the first time, had to go through graduation with the local television cameras whirring.

Rabbi Gutterman delivered an eloquent invocation and benediction, both addressed to God and both ending with Amen. The rabbi spoke of America’s diversity, the rights of minorities and the court system where everyone could seek justice.

Weisman was relieved when the audience applauded Deborah when her name was announced. “There were no boos, and that is what we had prepared her for. I had really been worried that she would experience something scarring.”

But as the case made it to the Supreme Court, they got threats from prank callers and anti-Semitic slurs in hate mail. Some Jewish friends urged them to drop the fight, fearing it would awaken anti-Semitism.

Deborah Weisman “hated” the attention but thought her family did the right thing. “You can stand up for what you believe in, and it may get hard, but you won’t die… They (people) didn’t seem to realize that we weren’t anti-religion. We’re just protecting our rights to be in a public school and not have religious views thrown in our face.”

The question the Weismans heard most often was why make such a big deal out of a little prayer.

Merith said, “I don’t think a little prayer is a small thing. It excludes.” Her father said, “They forced me to pray to someone else’s God. That is a big deal… When you go down that road of imposing religion on people there is no end to that road…”

“When I am forced to participate in a ritual, it is a violation of my human rights. It’s an attempt to make me different from what I am – to change my identity, to make me conform.’’

President George H.W. Bush’s Justice Department told the Supreme Court it should use the case to reduce the separation of church and state and accommodate more religion in the public square.

Most experts thought the court would take the invitation. It didn’t. Justice Anthony M. Kennedy surprised everyone and ruled for the Weismans. Kennedy may have surprised himself in that Supreme Court papers show that he had been writing a majority decision to uphold the prayer before deciding the decision didn’t look right.

Kennedy rejected the school’s claim that Deborah had a choice not to attend her graduation. He said that was not really a choice. And he said that the peer pressure that young people would feel to pray along with their friends imposed a subtle coercion that violated the First Amendment’s Establishment clause, separating church and state.

The Joneses and political correctness

Russell and Laura Jones were successful products of America’s grand experiment at racial integration – at least until the early morning hours of June 21, 1990 when Neo-Nazi skinheads burned crosses on their lawn.

Laura’s great-grandmother was murdered in the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi in the 1960s. Laura grew up in rural Minnesota and attending nearly all-white schools. She was called names, got into fights and her family was seldom included in neighborhood functions. But they persevered.

Laura’s great-grandmother was murdered in the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi in the 1960s. Laura grew up in rural Minnesota and attending nearly all-white schools. She was called names, got into fights and her family was seldom included in neighborhood functions. But they persevered.

Russell lived in the inner city but was bused to the white suburbs beginning in the fourth grade as part of an integration plan that put him in integrated schools through high school.

After marriage, Russell, a production control supervisor for Control Data Corp., and Laura, a waitress, decided they needed a bigger house in a safer neighborhood. Russell set one rule: Look anywhere but the East Side, a blue-collar neighborhood with a reputation for not welcoming blacks.

But the Joneses found a spacious two-story house on the East Side at 290 Earl St. with enough space for their five children. At first things were fine. Neighbors brought baskets for the children at Easter and a few people came to welcome them.

But a month after moving in, Russell found all four car tires slashed. A few weeks later, the back car window was shattered. Then on the way to church the family was confronted by three teens on the front walk, one with a Mohawk and another a shaved head.

“What are you looking at, n…..?” one asked Russell Jr., then 9. The boy, a sad and bewildered look on his face, asked what the word meant. Russell later told his son, “We can’t be doing anything about people like that… Just walk away and don’t confront them.”

Then came the first night of summer, a couple of hours after midnight. “I woke up because I heard voices,” Russell recalled. “They were whispering, but it sounded real close. I heard running, and I opened my eyes, and there was an orange glow. It went through my mind that they had started my car on fire. Instead, I see this cross burning in the yard.”

A 2-foot-by-2-foot cross made of furniture legs was burning in the side yard. “When you read about it or see how television depicts it, it is something you think you will never have to face. This night it happened, and I was scared for my family.”

At breakfast Laura spoke to the children. “I told them that something happened last night that wasn’t good. Some people burned a cross. They asked, ‘What does that mean?’ I said, ‘It means there are some people in the neighborhood that don’t like us here.’ They asked why. I said there are some people who don’t like black people here. Then I told them to stay in the yard and not wander around the block.”

TV news arrived. Mayor Jim Scheibel paid a visit. Neighbors, whom the Joneses hadn’t met, came to apologize and bring food. Police arrested two skinheads, one a 17-year-old juvenile, referred to in court files as R.A.V. The boys told police that the cross-burning had taken place after a discussion about “burning some n…….”

The Neo-Nazi cross burning on the Jones’ lawn became an important decision – R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul. But it was not a victory for justice for the Joneses. It was the Supreme Court’s warning against political correctness.

The law that St. Paul used to punish R.A.V. made it illegal to burn crosses, scrawl swastikas, or take other actions that arouse “anger, alarm or resentment” based on race, color, creed, religion or gender.

The issue came to the court when political correctness and campus speech codes were on many justices’ minds.

More than half the nation’s campuses had adopted rules to punish sexist and racist speech. That ignited a debate over “political correctness,” with conservatives complaining that they are censured for questioning liberal orthodoxies on affirmative action, women’s issues and gay rights.

Justice Antonin Scalia wrote the majority opinion in which he said the problem with the St. Paul ordinance was it protected some groups – like blacks and women – but not other groups. This discriminates based on the content and viewpoint

For example one could hold up a sign declaring all anti-semites are bastards but not that all Jews are bastards. The court said the government has no authority “to license one side of a debate to fight freestyle, while requiring the other to follow the Marquis of Queensbury Rules.”

No discrimination against Christian speech

Ronald Rosenberger and his friends wanted to start a Christian magazine at the University Virginia in 1990 and asked the university to pay $5,800 toward printing costs. University fees had gone to 118 student groups, including some with religious affiliations to Jews or Muslims.

But the university said no to the fee request because it feared providing money for the Christian magazine would violate the separation of church and state.

The magazine, Wide Awake, went to press but folded after four issues. The students’ court suit did much better.

In a 5-4 decision, the court ruled that the university rules discriminated against the viewpoint of the Christian students.

It was 1995 when the decision was handed down and the court was well on its way to extending the protection of free speech from the outsiders to insiders, conservatives and the well-heeled.

Past were the simple days of a unanimous court protecting Margaret Gilleo’s little sign and her stand against a president and a mayor. The more complicated clash of free speech with equality in the battle over political correctness lay ahead.

No Comments