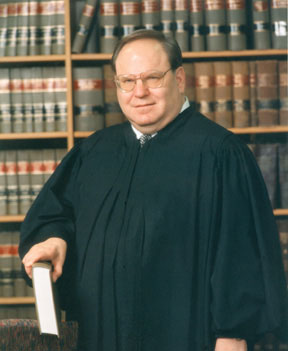

Missouri Supreme Court Judge Richard B. Teitelman was a friend equal justice, a friend of the Bill of Rights and a friend of the journalism review. He was a friend of mine and many others his life touched. This issue on the Bill of Rights is dedicated to Judge Rick who died last month.

If you have a mental image of a judge in your mind, forget it. Judge Teitelman was nothing like any other judge.

Michael Wolff, the outgoing dean of the Saint Louis University Law School and a former colleague of Teitelman’s on the court, described his friend this way in a column for the Post-Dispatch:

Michael Wolff, the outgoing dean of the Saint Louis University Law School and a former colleague of Teitelman’s on the court, described his friend this way in a column for the Post-Dispatch:

“Most mornings before a Missouri Supreme Court session was to begin, Judge Richard B. “Rick” Teitelman, a large disheveled man with big thick glasses and a smile to match, would appear in the courtroom and go around shaking hands making everyone feel welcome. Unusual for a supreme court judge, but it was perfectly in character for one of the most remarkable men I have ever known.”

If Teitelman knew that the wife or parents of one of the lawyers arguing a case was in the courtroom, he’d make special effort to say nice things about the argument, said Wolff.

Teitelman was the first Jewish judge on the Missouri Supreme Court and the first who was legally blind.

After graduating from Washington University Law School in 1973, Teitelman had to get a reader to take the bar. After passing he couldn’t get a job because of his blindness so he hung up his shingle outside his one-room apartment. Sometimes he took a bus to work.

His representation of farm workers during the grape boycott got the attention of Legal Services where he went to work. By 1980 he was executive director. There he inaugurated the Justice For All ball to raise money for legal services.

One reason Teitelman worked the room was to supplement his eyesight and figure out who was present. But Teitelman was genuinely interested in people.

A friend of his, emeritus professor Roger Goldman at Saint Louis University Law School, remembers a funny story. “He never missed an opportunity to talk to someone,” Goldman recalled. “Once I was walking on the SLU campus and I spotted Rick in conversation. When I got closer he was talking to the Billiken Buddha like sculpture! When I told him, he let out a big laugh and asked how I was doing.”

Teitelman dedicated his life to serious causes but he did not take himself too seriously.

Attorney David Camp clerked for Teitelman a decade ago. That job included driving him to Jefferson City for oral arguments. One day Teitelman asked him to start at 5 a.m. so they could stop by a little store in north St. Louis to pick up an order of sardines. The sardines were in a styrofoam container with a flimsy plastic lid. Teitelman told Camp is was “the good stuff. It’ll be my emergency stash.”

On Thursday after a week of oral arguments, the sardines were still there. “We load up my car and take off,” Camp recalls. “There, on my dash, he has placed the styrofoam container of 3-day-old unrefrigerated sardines. He always wanted me to drive as fast as possible. I would say ‘Rick, you’re blind, how can you even tell?’ He would say ‘I can hear cars that pass us, let’s go!’

“So, I’m weaving in and out, trying to pick up the pace, and Rick is pleased. He decides it’s time to eat, and opens the sardines container. Rick said ‘these are better with age’ and grinned at me. Just then, a truck cut me off and I hit the brakes, causing the sardines, and the sardine oil, to slosh just enough to escape the meager confines of the styrofoam container.”

After a weekend of trying to clean his car, Camp sold it. The next Monday Camp picked him up in another car. Teitelman was pleased. The new seat was more comfortable.

Teitelman often told the story on himself. “He said he liked the story because it showed how tenacious he was in finishing something, and in not being wasteful, and that his clerks were good at problem-solving.”

Another time Camp ran into Teitelman outside a suburban movie theater. Teitelman loved movies, watching from the front row. Camp asked if the judge would like to see a movie with him. Teitelman said he couldn’t. The theater had kicked him out thinking he was a vagrant because he had fallen asleep.

“Rick never did pull out his badge or explain his stature in such situations,” Camp recalled in an email. “I think he was Chief Justice at the time. He proposed that we go for a bite to eat instead – he always knew of a place. We did, and after our meal, he looked at me with a serious expression, leaning over so as not to be overheard: ‘we should go back to the theater now and try to get in, they just had a shift change!’”

At times, when clerks were having trouble finding precedent to back up an argument, Teitelman would tell them the story of a man he had represented as a young lawyer. The man had been arrested for shoplifting one can of dog food.

“The man had been caught in the act.” recalled Camp. “What was the defense? Well, that it was dog food, and that was to be his dinner. The man had used all his food stamps to feed his family, and gone to the grocery store to look for a dented dog food can, for his meal. He had a can opener in his pocket, and hoped to eat it before returning home to avoid the shame. He thought the store couldn’t sell the dented cans, and it wouldn’t do them harm. Upon hearing the full story, the prosecutor decided to drop the case.

“The lesson: always look at the whole story, the context, and how people are affected by the law. Rick believed the law must be formed to protect fundamental values of human decency and dignity.”

Teitelman reflected those values in important court decisions.

- The evolving standard of decency protected by the Eighth Amendment meant that juvenile murderers should not be executed, the Missouri Supreme Court decided. That decision paved the way for the U.S. Supreme Court ruling ending juvenile executions.

- The right to a jury trial, protected in the Missouri Constitution, meant that the legislature couldn’t cap awards for pain and suffering in medical malpractice cases.

- Manifest injustice was the reason to overturn the murder conviction of death row inmate Joseph Amrine. Amrine had been convicted in a fair trial of killing another inmate but all of the witness later recanted. The state argued the execution should go forward because the trial was fair. Teitelman wrote, “It is difficult to imagine a more manifestly unjust and unconstitutional result than permitting the execution of an innocent person.”

- The long history of civil rights progress – first desegregating schools, then striking down laws against interracial marriage and then outlawing sex discrimination – justified survivor benefits to the same-sex partner of Missouri Highway Patrolman Corporal Dennis Engelhard, killed in the line of duty.

“With the benefit of hindsight, the various decisions extending the guarantee of equal protection to racial minorities and women, though intensely controversial at the time, now seem obvious to a vast majority of Americans,” wrote Teitleman.

“Now that (they)…. are woven firmly into the fabric of constitutional law, this question remains: Why did it take so long?”

Teitelman wrote that passage in a dissent in 2013 because the majority of the court was not ready to take on Missouri’s ban on same-sex marriage. He was far-sighted. The U.S. Supreme recognized two years later that it had taken too long.

No Comments