The press is losing its power, its credibility and its way.

As the Bill of Rights turns 225, the one business it protects, the press, is suffering an identity crisis.

Who is a journalist? Is Julian Assange a publisher? By democratizing news does the Internet serve democracy or confuse it? By serving as a world wide communications system does the web draw us together or fracture us into warring factions? Should Facebook and other online social media take down false news or hate speech or alt-right advocacy or incitement against police?

Why didn’t voters heed the investigations and fact-checks of Donald Trump? Does adherence to journalistic neutrality obscure the truth in false equivalencies? Is Trump, with his morning tweets, playing the press by setting the news agenda? Should the press publish WikiLeaks’ stolen emails, even if it is effectively serving as an arm of Russian intelligence? How can professional journalists regain trust and distinguish their work from the fake news exploding on the Internet?

A 25 year fade

In 1991, on the 200th anniversary of the Bill of Rights, the press was at the height of its power and influence although people’s confidence was low.

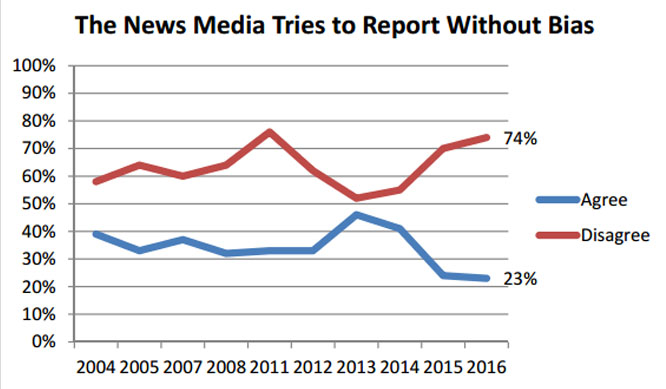

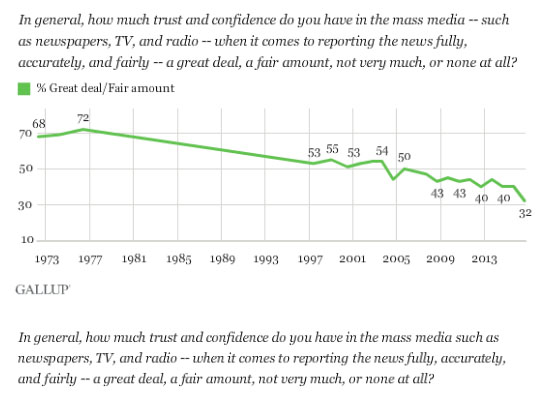

Now, 25 years later, the power and influence of the mainstream media have waned and the people’s trust has fallen even more precipitously. Just after Watergate, 72 percent of Americans had confidence in the press, according to Gallup. The number dropped to 55 percent in 1991. Now it’s 32 percent with only 26 percent of those under 50 saying they have confidence.

A majority of the youngest citizens, Millennials and Gen Xers, report getting most of their news about politics and government from Facebook, which isn’t a news organization.

The mainstream media have themselves to blame in part for the lost credibility. Jason Blair invented stories at The New York Times. Judith Miller reported for the Times on weapons of mass destruction that didn’t exist. Leading news organizations all but convicted the nuclear scientist Wen Ho Lee of espionage and Steven Hatfill of sending anthrax to Capitol Hill. Neither accusation was true.

Meanwhile the legacy media were sidetracked by the biggest revolution in communications technology since Guttenberg’s movable press half a millennium ago. Science put magical devices in everyone’s pocket that permitted instantaneous communication.

The list of new communications devices, institutions and communication terms is endless – citizen journalist, smartphone, GPS, social media, Google, Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, Instagram, Periscope, livestream, tweet, aggregate, link, likes, impressions, shares, comments, friends, followers, page views, click bait, fake news, big data, Drudge, Breitbart, alt-right, Huffington Post, Fox, MSNBC, chatbots, WikiLeaks, Google Earth, Google Street View, virtual reality, photoshop, face recognition software.

As news media platforms explode, the press is having a nervous breakdown that echoes through the public space and challenges democratic processes. The word – press – is itself an anachronism as printing presses close across the country.

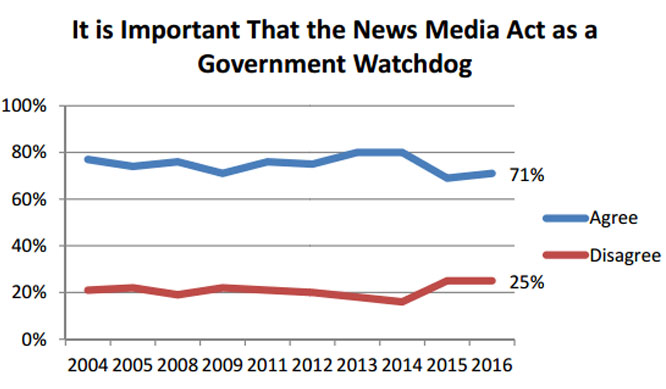

The number of reporters in newsrooms has declined by 20,000 in the past decade. That is a decline of about 40 percent, from 54,000 to 33,000. With each buyout and layoff, news organizations lose the muscle to serve as watchdogs.

More than 120 daily newspapers have closed since 2004 and print advertising is falling off a cliff. It was down 8 percent last year nationally, according to a Pew study, with print advertising at The New York Times down double digits.

Existential crisis

But the crisis runs deeper than closed newspapers and empty newsroom desks.

Christiana Amanpour, the CNN foreign correspondent, said a month after the presidential election that journalists face an existential crisis. She said:

“We have to accept that we’ve had our lunch handed to us by the very same social media that we’ve so slavishly been devoted to.

“The winning candidate (Trump) did a savvy end run around us and used it to go straight to the people. Combined with the most incredible development ever–the tsunami of fake news sites–aka lies–that somehow people could not, would not, recognize, fact check, or disregard.

“…Facebook needs to step up…I feel that we face an existential crisis, a threat to the very relevance and usefulness of our profession…”

“In the same way, politics has been driven into poisonous partisan and paralyzing corners…that same dynamic has infected powerful segments of the American media…Journalism itself has become weaponized. We have to stop it.”

A decade ago, Cass Sunstein, a First Amendment expert, foresaw potential dangers ahead. “As a result of the Internet, we live increasingly in an era of enclaves and niches—much of it voluntary, much of it produced by those who think they know, and often do know, what we’re likely to like,” Sunstein said in 2007. “If people are sorted into enclaves and niches, what will happen to their views? What are the eventual effects on democracy?”

Powerful democratizing force

Is Amanpour right or is this handwringing by overwrought liberal reporters who wouldn’t see a crisis if Hillary Clinton had won?

In many ways the Internet and social media are miracles of science and engineering. They are powerful democratizing forces that allow outsiders to go over the heads of media elites and get their story out to the country and world.

The outsiders might be the Black Lives Matter protesters alerting the nation and the world to police abuse of African-American men. Or they might be conspiracy theorists who think 9/11 was a U.S. orchestrated intelligence operation or that the massacre of first graders at Sandy Hook was a fictional Hollywood production designed to take away people’s guns.

Trump used Twitter in very much the same way as Black Lives Matter, getting information to the masses by bypassing or hijacking traditional media.

It may be that the problem with 2016 election coverage was less the Internet and more the habitual failings of the mainstream press.

Thomas Patterson, in a report for the Harvard’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, put his finger on the high level of negativity in the press coverage of both Trump and Clinton. The report showed that only about 10 percent of the presidential election coverage involved policy; about 60 percent focused on the horse race or controversies.

Patterson said, “an incessant stream of criticism has a corrosive effect. It needlessly erodes trust in political leaders and institutions and undermines confidence in government and policy.”

Fake news

The 2016 presidential election campaign featured an unprecedented amount of fake news online. Both liberals and conservatives were guilty, although Buzzfeed found that hyper-conservative sites had a higher percentage of false or mostly false stories than hyper-liberal ones.

Buzzfeed also found that the entirely false news stories from fake news sites got more attention on Facebook than the top real stories.

“In the final three months of the US presidential campaign,” it concluded, “the top-performing fake election news stories on Facebook generated more engagement than the top stories from major news outlets such as the

New York Times, Washington Post, Huffington Post, NBC News, and others,”

Among the fake stories getting the most traction were those claiming the pope endorsed Trump, Clinton sold weapons to ISIS and that an FBI agent investigating Clinton’s emails had been found dead. One of the fake stories about Trump claimed the “surgeon general of the US warned that drinking every time Trump lied during the first presidential debate could result in acute alcohol poisoning.”

Pizzagate

The gunfire at the Comet Ping Pong pizza restaurant in Washington,D.C. on Dec. 4, 2016 illustrates how fake Internet news, entangled with politics, can have dangerous consequences. The Washington Post retraced the origins of the false story:

In late October and November, more than one million tweets contained the twitter handle “pizzagate.” It referred to an Internet conspiracy that Hillary Clinton was involved in a child sex ring operating out of the basement of a popular Washington, D.C. pizza place called Comet ping pong. (The restaurant had ping pong tables but no basement.)

Alex Jones, the right-wing conspiracy theorist and Trump supporter jumped into the controversy with a YouTube video stating Hillary Clinton was “involved in a child sex ring” and had “personally murdered, chopped up and raped” children. The video was viewed 427,000 times.

The Friday before the election, the owner of Comet pizza got streams of comments on his Instagram calling him a pedophile. An online conversation on 4Chan and Reddit claimed a child sex operation was being run out of the restaurant with children held in the basement. Nearby shops also began getting threats.

The hashtag #pizzagate was retweeted hundreds or thousands of times each day from places like the Czech Republic, Vietnam and Cyprus. Bots – programs designed to promote tweets – composed many of the retweets.

On Nov. 16, Jack Posobiec, former Naval Reserve intelligence officer involved in a pro-Trump organization, went to Comet to investigate. He walked into a back room where a child’s birthday party was underway and started to livestream it to a worldwide audience on the Periscope app. The restaurant forced him to leave.

He explained: “People have lost faith with government and the mainstream media being any real authority…If I can do something with Periscope and show what I’m seeing with my own two eyes, that’s helpful.”

On Sunday, Dec. 4, Edgar Maddison Welch decided to self-investigate. He walked into the restaurant with an assault rifle and handgun looking for the children and tunnels. After about 45 minutes, firing the gun but finding nothing, he surrendered.

The Post concluded that Pizzagate was “possible only because science has produced the most powerful tools ever invented to find and disseminate information.”

The First Amendment

The classic liberal response to false and hateful speech is more speech. As Justice Louis Brandeis put it in 1927, “If there be time to expose through discussion the falsehood and fallacies, to avert the evil by the processes of education, the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence.”

Critics have called upon Facebook to exercise greater editorial control, now that it has become the world’s most influential publisher. And there are indications that it is moving that direction. Facebook has appointed a task force to look into the fake news and Google will bar fake news sites from its AdSense advertising program, cutting off revenue.

But Nicholas Lemann of The New Yorker doesn’t think Facebook is up to the task. ‘It’s a sign of our anti-government times that the solution proposed most often is that Facebook should regulate it. Think about what that means: one relatively new private company, which isn’t in journalism, has become the dominant provider of journalism to the public, and the only way people can think of to address what they see as a terrifying crisis in politics and public life is to ask the company’s billionaire C.E.O. to fix it.’

Lemann has different idea: “If people really think that something should be done about the fake-news problem, they should be thinking about government as the institution to do it.”

That, however, runs smack into the First Amendment. The Supreme Court provides the Internet the same high level of protection as a newspaper. Any government action to sort out and punish fake or misleading news would most likely be unconstitutional.

On one thing Lemann is right. This problem of fake news is not new. Joseph Pulitzer saw the danger more than a century ago when he issued this warning about what would happen well-educated journalists:

“Our Republic and its press will rise or fall together,” Pulitzer wrote. “An able, disinterested, public-spirited press, with trained intelligence to know the right and courage to do it, can preserve that public virtue without which popular government is a sham and a mockery. A cynical, mercenary, demagogic press will produce in time a people as base as itself. The power to mould the future of the Republic will be in the hands of the journalists of future generations.”

Arthur Miller, the playwright, put it more colloquially. “A good newspaper, I suppose, is a nation talking to itself.”

Twenty years from now there probably won’t be daily papers delivered on people’s lawns. But the electronic and digital media that remain need to find a way to help the nation talk to itself again.

No Comments